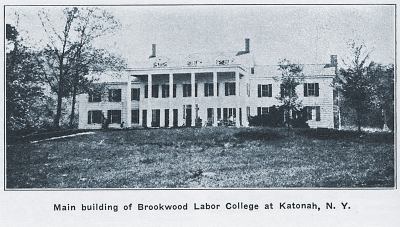

Between 1918 and 1921, various groups associated with the labor movement in the United States founded at least 20 colleges and institutes geared specifically towards workers.1 These schools were not intended to function as “mass-education providers” like conventional colleges and universities did, but instead sought to cultivate activists and leaders that would then work towards the collective goals of the labor movement. From 1921 to 1937, Katonah, in northern Westchester County, was home to Brookwood Labor College, one of the centers of the workers’ education movement.

On March 31, 1921, a group of labor leaders convened in Katonah to discuss establishing a residential college for workers.2 They had been summoned by William Fincke, a wealthy Katonah resident, on whose property the college would be constructed. Brookwood was founded on four central tenants:

- A new social order was needed and was already on its way.3

- Education would hasten the coming of said new social order, while reducing or potentially eliminating the need for violence.

- Workers would be the ones to bring about the new social order.

- There was an immediate need for a workers’ college with a broad curriculum in a country setting, where students could fully apply themselves to learning.

The founders of Brookwood argued that workers’ education was necessary because current educational institutions failed to meet working-class needs. Aside from the general lack of educational opportunities available to working class people, labor leaders criticized existing public schools for their hostility towards workers.4 For example, James H. Maurer, one of Brookwood’s founders and the president of the Pennsylvania Federation of Labor, compared his personal experience in public schooling to a penal institution that instilled anti-labor attitudes in children.

Many of Brookwood's founders were Socialists or had Socialist leanings, and the College was certainly heavily influenced by Socialist ideology. Despite this, Brookwood remained committed to a “factual approach to the study of social problems through dispassionate but critical presentation and discussion of the subject matter,” according to David Saposs, an instructor at the College.5 While Brookwood was undoubtedly and openly loyal to labor as opposed to Capitalist interests, the College intentionally avoided factionalism within the labor movement. In a New York Times article from 1931, AJ Muste, the then dean of the College, is quoted describing Brookwood’s commitment to freedom in education:

“We have tried very hard to not be dogmatic in our educational work, not to force ideas down our students’ throats, to discuss and analyze the theories and policies of all elements in the labor movement, and encouraged the students to form their own opinions in regard to them.”6

Brookwood hosted guest lectures and teachers from various political persuasions within organized labor and intentionally recruited students that would disagree with each other.7

Brookwood’s curriculum heavily stressed the social sciences, as those disciplines were deemed most relevant to labor organizing.8 During their two years at Brookwood, students’ coursework typically consisted of theoretical classes that gave them the necessary background to understand the social, political, and economic forces of the world, and “tool” courses that were more centered on practical skills.9 In a New York Times article from 1921, AJ Muste explains that during students’ first year they would take a history class to “show the social forces at work through the masses;” an English course adjusted to a student’s existing literacy and skill; argumentation, with weekly debates, “so that they may learn to express what they wish clearly and logically;” and an economics class covering the “branches necessary (such as child labor and unemployment) to the proper development of a labor leader.”10 Students’ second year would be more specialized to their specific interests and strengths. Potential second year courses included social psychology, labor tactics, statistics, and labor journalism. A 1929 New York Times article lists an expanded course catalog including foreign labor, parliamentary law, American labor history, and future plans to include correspondence, workers’ education, and union organization.11 Aside from their work in the classroom, students at Brookwood were encouraged to participate in off-campus field work. Joining picket lines and other organizing activities gave students hands-on practical experience that would prepare them for future labor organizing.12

Theater was another prominent aspect of life at Brookwood. Converting an old barn into a stage, the College started its labor drama program in the fall of 1925.13 For Brookwood students, Labor drama was both a means of self expression and a way of propagandizing for the labor movement. Students and teachers alike wrote and staged plays centering around themes of class struggle, unionization, solidarity, and working class life, generally within an urban setting. Throughout the late 1920s up until Brookwood’s closing in 1937, students would tour the United States performing their plays. In 1934 they visited 53 cities, performing for around 14,500 people.14 In 1935 students staged 90 performances for an estimated 22,000 people.15

Brookwood was also remarkable for its all-encompassing democratic and anti-hierarchical approach to education. Classes mainly consisted of open discussions as opposed to lectures, which were considered unnecessarily authoritative.16 Teachers would attempt to remain as neutral as possible, encouraging students to come to their own conclusions. Relationships between students and their instructors were markedly informal and egalitarian. Younger teachers were often referred to by their first name, and students and faculty were both responsible for on-campus chores.17 It was also common for students and their instructors to participate in extracurricular recreational activities together, such as sports and theater. Outside of the classroom, students held important decision making roles at Brookwood, including two designated seats on the board of directors.

Generally speaking, students at Brookwood were in their twenties and from a working class background.18 Admissions requirements were relatively minimal, asking only that prospective students be workers committed to trade unionism, and that they provide three references.19 The student body at Brookwood was remarkably inclusive, especially for the early 20th century, as it was both coeducational and integrated, including women, black, and immigrant students.

Despite its initial popularity within American labor, in the late 1920s Brookwood began to draw criticism from more conservative currents within the movement, especially the American Federation of Labor. In 1927 the AFL began a secret investigation into the College, aiming to uncover “radicalism” and Communist sympathies.20 A year later, the AFL officially denounced Brookwood and called on its affiliated unions to withdraw their support for the College.21 The AFL asserted that besides being overly sympathetic to Communism, Brookwood was also disloyal to the AFL and encouraged “anti-religious” beliefs in its students. Brookwood also had its detractors among the more radical wing of the American labor movement. Communists contended that the College was counter-revolutionary and reformist, and that its faculty was made up of “petty-bourgeois social democrats.”22

Though Brookwood remained relatively undaunted by its critics, the College began to face financial issues in the early 1930s amid the Great Depression.23 This combined with factionalism within the Brookwood community and low enrollment led to the school’s closing in 1937.

Despite Brookwood’s short tenure, the College produced many graduates that would go on to become important figures within labor and other movements for years to come. Pauli Murray was already an experienced activist when she enrolled at Brookwood hoping to learn more about organizing the Black community in New York City around labor.24 During her time at Brookwood, Murray deepened her understanding of how racial injustice and workers’ oppression were interconnected, and how any attempt to rectify one of these issues would have to account for the other. After graduating from Brookwood, Murray went on to become a writer, activist, civil rights lawyer, and feminist theorist, among other endeavors.25 She became friends with Eleanor Roosevelt, influenced the creation of the National Organization of Women, and was the first Black woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest. Her 1950 book, States’ Laws on Race and Color addressed the unconstitutionality of segregation, and became the bedrock for arguments posed in Brown v. Board of Education.26

After graduating from Brookwood, Sadie Goodman, a Jewish immigrant from Britain, moved to Philadelphia to work for the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA). In the early 1930s Goodman traveled to Los Angeles and helped build the Western School for Industrial Workers alongside the YWCA, jump starting an explosion of labor colleges similar to Brookwood on the West Coast.

Sarah Rozner was a Jewish Hungarian immigrant to Chicago who’d been drawn to the labor movement during a 1910 garment worker strike.27 After graduating from Brookwood, she moved back to Chicago, where she organized alongside Sadie Goodman for women’s greater role in the ACWA.

Len De Caux became associated with the labor movement after he moved to the United States from New Zealand and started writing for various labor publications.28 As one of Brookwood’s earlier students, he attended the college from 1922 to 1924. After graduating, he continued to work as a labor journalist, taking positions at the UMW Illinois Miner, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers Journal, and the Federated Press. In 1935 he became the publicity director at the Congress of Industrial Organization, where he worked until 1947.

After graduating from Brookwood, Walter P. Reuther went on to be one of the most influential people in 20th century American labor.29 In 1946 Reuther was elected president of the United Auto Workers, and under his leadership, workers experienced massive wins, such as supplemental unemployment benefits.30 In 1952 he was elected president of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, where he served until 1968.

Reuther was also committed to civil rights, supporting the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and marching alongside Dr. Martin Luther King.

From 1921 to 1937 Brookwood Labor College created a hub for left-wing and labor politics in Westchester County. The College created valuable educational opportunities for working class people whose needs had been neglected by existing public and private schools. Brookwood created an intellectually rich environment where workers could immerse themselves in a number of perspectives while developing important skills that would help them organize alongside their fellow workers for better conditions. Despite the College’s critics and its closing in 1937, graduates went on to become important figures within labor and other 20th century movements, fighting for social change and legislation that still impacts people’s lives today.

Endnotes.

1 Tobias Higbie, “‘To See and Hear Things That Have Always Been There’: Labor’s Pedagogy of the Organized,” in Labor’s Mind: A History of Working-Class Intellectual Life, 61–84. University of Illinois Press, 2019, https://doi.org/10.5406/j.ctv9b2x1j.8.

2 “Radical School in Westchester: Katonah to Have an Experimental Educational Institution Conducted With Socialistic Leanings,”

The Yonkers Herald, April 1, 1921, via Yonkers Public Library, https://yplonsite.newspapers.com/image/676821376.

3 ‘Plan Workers’ College: Fitzpatrick and Foster, Steel Strike Leaders, Among Promoters,” The New York Times, Apr. 1, 1921.

4 Richard J. Altenbaugh, “‘The Children and the Instruments of a Militant Labor Progressivism:’ Brookwood Labor College and the American Labor College Movement of the 1920s and 1930s,” History of Education Quarterly 23, no. 4 (1983): 395–411, https://doi.org/10.2307/368076.

5 David J. Saposs, “Labor,” American Journal of Sociology 34, no. 6 (1929): 1012–20 ,http://www.jstor.org/stable/2765888.

6 “Brookwood College Ends 10th Year Soon: Labor Institution at Katonah to Celebrate–Muste Reviews Factors that Brought Success,” The New York Times, Jan 25, 1931.

7 Leilah Danielson, “Pragmatism and ‘Transcendent Vision,’” In American Gandhi: A. J. Muste and the History of Radicalism in the Twentieth Century, 65–96, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7zw7rg.7.

8 Richard Dwyer, “Workers’ Education, Labor Education, Labor Studies: An Historical Delineation,” Review of Educational Research

47, no. 1 (1977): 179–207, https://doi.org/10.2307/1169973.

9 Richard J. Altenbaugh and Henry Rosemont, Review of “Our Children are Being Trained like Dogs and Ponies:” Schooling, Social Control, and the Working Class, by Walter Feinberg and Paul C. Violas, History of Education Quarterly 21, no. 2 (1981): 213–22, https://doi.org/10.2307/367693.

10 “Labor Statesmen’s Alma Mater Open: Brookwood, at Katonah, Aims to Develop Intellects of Promising Practical Workers,” The New York Times, Oct. 9, 1921.

11 “37 Enroll in Brookwood: Labor College to Open on Monday With Faculty of Six,” The New York Times, Oct. 12, 1929.

12 Richard J. Altenbaugh and Henry Rosemont, Review of “Our Children are Being Trained like Dogs and Ponies:” Schooling, Social Control, and the Working Class.

13 Richard J. Altenbaugh, “Proletarian Drama: An Educational Tool of the American Labor College Movement,” Theatre Journal 34, no. 2 (1982): 197–210, https://doi.org/10.2307/3207450.

14 Peter Seixas.

15 “Anniversary Fete Planned By Brookwood Labor College: School Which Shuns Athletics and Proms, To Mark 15th Birthday–Out of 50 Recent Graduates 22 Have Been Arrested for Labor Activities,” The New York Times, Jun. 20, 1935, https://yplonsite.newspapers.com/image/677043408.

16 Leilah Danielson, “Pragmatism and ‘Transcendent Vision.’”

17 Richard J. Altenbaugh, “‘The Children and the Instruments of a Militant Labor Progressivism:’ Brookwood Labor College and the American Labor College Movement of the 1920s and 1930s.”

18 Richard J. Altenbaugh and Henry Rosemont, Review of “Our Children are Being Trained like Dogs and Ponies:” Schooling, Social Control, and the Working Class.

19 Richard J. Altenbaugh, “‘The Children and the Instruments of a Militant Labor Progressivism:’ Brookwood Labor College and the American Labor College Movement of the 1920s and 1930s.”

20 Tobias Higbie, “‘To See and Hear Things That Have Always Been There’: Labor’s Pedagogy of the Organized.”

21 Richard J. Altenbaugh, “‘The Children and the Instruments of a Militant Labor Progressivism:’ Brookwood Labor College and the American Labor College Movement of the 1920s and 1930s.”

22 David J. Saposs, “Labor.”

23 Richard J. Altenbaugh, “‘The Children and the Instruments of a Militant Labor Progressivism:’ Brookwood Labor College and the American Labor College Movement of the 1920s and 1930s.”

24 Tobias Higbie, “‘To See and Hear Things That Have Always Been There’: Labor’s Pedagogy of the Organized.”

25 Keneth W. Mack, “Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt’s Beloved Radical,” The Boston Review, Feb. 29, 2016, https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/kenneth-mack-patricia-bell-scott-firebrand-first-lady-pauli-murray-eleanor-roosevelt/.

26 “Jane Crow & the story of Pauli Murray,” National Museum of African American History & Culture, accessed Jun. 22, 2023, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/jane-crow-story-pauli-murray.

27 Tobias Higbie.

28 “The Len and Caroline Abrams Decaux Collection,” Wayne State University, accessed Jun. 22, 2023, https://reuther.wayne.edu/files/LP000832.pdf.

29 Nelson Lichtenstein, “Assessing 40 years of Labor Notes,” Center for the Study of Work, Labor, & Democracy, University of California - Santa Barbara, Apr. 8, 2019, https://labor.history.ucsb.edu/news/announcement/543.

30 “Walter P. Reuther,” Wayne State University, accessed Jun. 22, 2023, http://reuther100.wayne.edu/bio.php?pg=3.

YPL Resources about Organized Labor

Please use this link to find print and electronic resources about organized labor in our library catalog. Please contact us at localhistory@ypl.org if we might help with your research, or if you'd like to learn more about our local history resources.

This article was researched and written by Laurel Collins, CLIP intern at Yonkers Riverfront Library through Sarah Lawrence College.