In May of 1970 Sarah Lawrence students participated in another wave of radical political action. On May 4th, an editorial, with contributions from students at 11 East Coast colleges and universities, including Sarah Lawrence, was published in The Columbia Spectator denouncing Richard Nixon’s decision to send American troops to Cambodia and to resume bombing North Vietnam.56 The editorial then called on “the entire academic community of this country to engage in a nationwide university strike.” The proposed strike was meant to be “a dramatic symbol of … opposition to a corrupt and immoral war,” recognizing that “within a society so permeated with inequality, immorality and destruction a classroom education becomes a meaningless and hollow exercise.” The editorial was not merely an announcement that students at the 11 institutions–Brown, Bryn Mawr, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Harvard, Haverford, Princeton, Rutgers, Sarah Lawrence, and the University of Pennsylvania–would be striking, but was meant to be a rallying cry for students across the country to join in a nationwide strike. In the words of the editorial, “a massive, unprecedented display of dissent (was) required.”

That same day, the Governor of Ohio had declared martial law at Kent State University following days of unrest on campus.57 Because of this, an anti-war rally that was scheduled for noon that same day had become illegal. Still, hundreds of students attended, and at 12:25 pm the Ohio National Guard fired 61 shots into the crowd, killing four students. This instance only fueled students’ anger, and in the next few days over a million students at over 800 schools would go on strike.58

The demands of the National Student Strike were as follows:

- “That the United States government end its systematic oppression of political dissidents, and release all political prisoners such as Bobby Seale and other members of the Black Panther Party.”59

- “That the United States Government cease its escalation of the Viet Nam war into Cambodia and Laos; that it unilaterally and immediately withdraw all forces from Southeast Asia.”

- “That the universities end their complicity with the United Slates war machine by an immediate end to defense research, ROTC, counterinsurgency research, and all other such programs.”

Sarah Lawrence officially joined the National Student Strike on May 5th. Out of 634 referendum participants including students, faculty, employees, and administrators, 539 voted to join the Strike, 55 voted against the Strike, 20 abstained, and 20 expressed mixed opinions. Immediately following the referendum, a permanent strike committee consisting of 11 students formed, two of which were sent to Washington DC to represent Sarah Lawrence at the National Student Strike Committee.60 In addition to the three main demands of the National Strike, Sarah Lawrence students insisted that colleges recognize the Strike as a valid academic activity.61 The official strike program at Sarah Lawrence consisted of organizing the college to take a stand as an institution, creating and distributing leaflets, community teach-ins, canvassing and community work, unifying anti-war groups, draft resistance and counseling, assisting other groups in organizing their own strikes, enlisting speakers for the college and surrounding communities, and utilizing students’ materials and talents for publicity campaigns.62

On the morning of May 6th Sarah Lawrence students gathered outside of the Mount Vernon Draft Board to hand out leaflets with information on how to get help with the Selective Service to young men going to their preinduction physical exams.63 Later that day, students canvassed and handed out leaflets in shopping areas in Bronxville, Mount Vernon, and Yonkers. Also on May 6th, Sarah Lawrence faculty voted 52-2 with 2 abstaining to support the Strike, giving full academic credit and no penalty to students engaged in political activity connected to the Strike.64 On May 7th students organized a committee to help campus employees with cleaning and kitchen work so that they would have time to participate in Strike activities. The same day, Sarah Lawrence students held an organizational meeting with other striking students in Westchester County and Long Island.

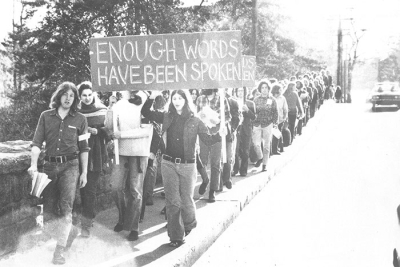

On May 8th, Sarah Lawrence students participated in a march “in memory of the four students killed at Kent State University and the Black men, women, and children of America who have died in their efforts to obtain freedom and equality in an intractable white society” in Yonkers.65 Students also engaged in a letter writing campaign to “swamp Washington with mail protesting Nixon’s actions here and abroad, and supporting the Hatfield-McGovern Amendment,” which was reportedly highly successful, as by May 8th, over a thousand letters had been sent.66 Students continued their canvassing and leafleting efforts to connect with people in the surrounding communities on a more personal basis, and “show ‘middle America’ that college students and people with differing political perspectives are human beings.” An Education Committee was also established in order to organize workshops and a Bookstore that would hold a reading room and literature from the Black Panther Party.

By May 9th striking students at Sarah Lawrence had gotten connected with local high schoolers who had carried out their own successful strike activities.67 Also on May 9th, nearly 100 members of the Sarah Lawrence community traveled to Washington DC to attend an anti-war rally.68 Though students appreciated the feeling of solidarity at the rally, they concluded that mass demonstrations like the one in Washington wouldn’t be as effective as organizing locally. By May 12th, canvassing had become the main priority of the Sarah Lawrence Strike.69 The same day a paragraph in The Emanon encouraged female students, who wouldn’t have been eligible for the draft in any case, to send letters to the draft board informing them that they would not be registering, signing with their first initial and last name. The goal was to sabotage the draft boards, as they were legally required to investigate every letter, wasting their time and resources.

On May 13th, Sarah Lawrence students joined a nation-wide boycott of Coca-Cola and Philip Morris Company products following a decision by the Economic Action Committee of the National Strike Coordinating Committee.70 The two companies were chosen for their pro-war lobbying, imperialistic policies, conservative executives, and racist policies. Striking students at Sarah Lawrence continued to work with other local schools, namely Concordia College, Marymount College, Iona University, the College of Mount Saint Vincent, Briarcliffe College, Manhattanville College, Dominican University, the New School, Orange County Community College, and Fairfield University.

Around this time, striking students began to experience pushback from local community members, with an editorial in the Bronxville Review Press-Reporter accusing students on strike of wanting to “shut down every campus in the country indefinitely, if not permanently–along with every other institution or operation of the ‘establishment’,” stating that “the names of the game (in the Strike) are anarchy and revolution.”71 On May 17th, The Emanon reported that there had been a “Whip a Hippy Day” in Yonkers.72 This opposition did little to hinder strike activities.

On May 20th, a group of 20 Sarah Lawrence Students went to Grand Central Station dressed up as realistic-looking war casualties to make a statement about the human cost of the war.73 The purpose of the demonstration was to “shock liberal businessmen into understanding what words and statistics can no longer communicate.” Students in plainclothes passed around anti-war leaflets to passers-by during the demonstration. On May 24th, the Sarah Lawrence Chorus gave a benefit concert at Scarsdale High School, with assistance from musicians from the University of

Massachusetts Amherst, Yale, Vassar, and Juilliard to raise funds for Strike activities.74 A group of students calling themselves Arts for Peace also gave performances of anti-war and anti-racist poetry, songs, and dance around Westchester County, also to raise money for Strike activities.75 On May 27th, 28th, and 29th, the Sarah Lawrence Dance Program held benefit concerts for the Black Panther Party’s Defense Fund.76

Throughout the duration of the Strike, Sarah Lawrence students placed heavy emphasis on local community involvement. From the start, students established a free childcare center on campus, enabling local parents, especially mothers to attend teach-ins and participate in other Strike activities.77 From May 11th to June 4th, the Strike Committee hosted a series of seminars, film screenings, and speakers on campus, all of which were open to the community.78 Within the Sarah Lawrence

community, students set up a Committee to Relieve the Staff, encouraging students and faculty to clean their own spaces in order to free up time for campus employees to participate in the Strike.79 At one point, someone from the Strike Committee called into the student radio station to explain that the Strike was meant “not to close down, but to open up the College,” establishing Sarah Lawrence as a “nerve and information center for antiwar activities.”80

The League for Industrial Democracy, Students for a Democratic Society, and the National Student Strike represent an increasingly forgotten, yet important history of

left-wing and radical politics on college campuses across the country. Sarah Lawrence still maintains a reputation of political progressiveness, which this tradition of student political activity arguably created. Though Sarah Lawrence students have been comparatively politically dormant for the past few years, there are still a few active groups on campus. Common Ground, for example, creates a physical space on campus for student of color identity groups and works to facilitate discussions around “the perceptions, realities, and consequences of racial and ethnic identity in our society and in the global context.”81 The Democracy Matters chapter at Sarah Lawrence centers itself on voting rights and eliminating “big money” from politics. The Green Rights Organization for the World focuses on environmental sustainability. Peace Action SLC promotes “peace, global understanding, and human rights.” Planned Parenthood Generation Action educates students about sexual health and reproductive rights.

Right-to-Write facilitates creative writing workshops for incarcerated people at the Westchester County Correctional Facility. SLC UNIDAD creates a safe space on campus for the Latine community. Dark Phrases is a student publication dedicated to amplifying the voices of people of color on campus. Other groups on campus include, the Disability Alliance, Harambee (a Black students’ union), the LGBTQIA Space, Queer People of Color, Queer Voice Coalition, Trans Action, Women of Color United, Student of Color Alliance, Asian American Culture Club, the Food Sharing Space, Jewish Voice for Peace, Students for Justice in Palestine, and the Sexual Violence Awareness & Education Subcommittee, among others.

This article was researched and written by Laurel Collins, CLIP intern at Yonkers Riverfront Library, a rising sophomore at Sarah Lawrence College.

End Notes

56 “An Editorial,” The Columbia Spectator (New York City, NY), May 4, 1970.

57 J. Gregory Payne, Ph.D., “Chronology,” May 4 Archive, 1997, https://web.archive.org/web/20030518120127/http://www.may4archive.org/chronology.shtml.

58 Amanda Miller, “May 1970 Antiwar Strikes,” Mapping American Social Movements, University of Washington, accessed Jul. 12, 2023, https://depts.washington.edu/moves/antiwar_may1970.shtml.

59 “Special Issue,” The Emanon, May 6, 1970.

60 Betsy Hanger, “College Joins Nation-Wide Strike,” The Emanon, May 7, 1970.

61 Sarah Lawrence College Strike Press Release, May 1970, Student Protest and Activism Collection, Sarah Lawrence College Archives.

62 Sarah Lawrence College: Program For Action, May 1970, Student Protest and Activism Collection, Sarah Lawrence College Archives.

63 “Special Issue.”

64 “Special Issue,” The Emanon, May 7, 1970.

65 “March in memory of the four students killed at Kent State University and the Black men, women, and children of America who have died in their efforts to obtain freedom and equality in an intractable white society,” May 7, 1970, Student Protest and Activism Collection, Sarah Lawrence College Archives.

66 The Emanon, May 8, 1970.

67 “High School Students Meet At Sarah Lawrence,” The Emanon, May 9, 1970.

68 “Washington: ‘Hot’, ‘Sad’, ‘Hopeful’,” The Emanon, May 11, 1970.

69 “Canvassing Top Priority,” The Emanon, May 12, 1970.

70 “Boycott Begun; Coke, Philip Norris Targets,” The Emanon, May 13, 1970.

71 “Editorial Comment: Colleges Are For Studying,” Review Press-Reporter, May 14, 1970.

72 “Special Issue,” The Emanon, May 17, 1970.

73 “Special Issue,” The Emanon, May 21, 1970.

74 “Special Issue,” The Emanon, May 15, 1970.

75 “Strike Sheet,” The Emanon, May 22, 1970.

76 Dance Group Concert, May 1970, Student Protest and Activism Collection, Sarah Lawrence College Archives.

77 Child Care Center, May 1970, Student Protest and Activism Collection, Sarah Lawrence College Archives.

78 Sarah Lawrence Strike Committee Press Release, May 1970, Student Protest and Activism Collection, Sarah Lawrence College.

79 To: All Faculty From: The Committee to Relieve the Staff, May 1970, Student Protest and Activism Collection, Sarah Lawrence College.

80 Called into Radio Stations, May 6, 1970, student Protest and Activism Collection, Sarah Lawrence College.

81 “Organizations,” Sarah Lawrence College, accessed Jul. 27, 2023, https://getinvolved.sarahlawrence.edu/organizations.