When you think of “the Y,” what pops into your head? A catchy song you used to hear at the disco? Swimming at the community pool? The YMCA (the Young Men’s Christian Association) has had a huge impact on both nationwide popular culture and localized community building.The YMCA was founded in 1844 by an Englishman named George Williams. Williams wanted to provide a place for young men who were being drawn to London by the Industrial Revolution to encourage the practice of Christian values. The YMCA was, for Williams and his supporters, an organization that would “preserve youth from the temptations of alcohol, gambling, and prostitution and that would promote good citizenship.”1 Eventually, the YMCA became based in Geneva with branches all over the world. Although their services provided young, working class men with opportunities for recreation and housing, the YMCA denied women entry to their programs. Despite the large number of women working in industrial facilities during this time period, it wasn’t until eleven years later that a comparable organization was formed to provide women with the same safety net offered by the YMCA.

In 1855, the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) was founded with the goal of protecting single women who migrated to urban areas to become part of the industrial workforce. Like the YMCA, the YWCA was founded in England. However, it only took three years for the YWCA to establish itself in the United States. YWCA USA is “dedicated to eliminating racism, empowering women and promoting peace, justice, freedom and dignity for all.”2 The YWCA’s mission to eliminate racism in the United States began years before its official attempt to integrate the organization in 1946. The YWCA’s founding principle to provide for women working in the industrial sector was put to the test during the first World War. During a time of social upheaval, areas of the YWCA slowly shifted to an ethic of peaceful and cooperative interracial relations.

In April of 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. Joining the Allied Powers of Great Britain, France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Canada, and Japan, the U.S. mobilized over 4.7 million military personnel against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire.3 While the U.S. armed forces entered the battlefield, a new demographic of citizens entered the industrial workforce - many of whom were educated and protected by the YWCA. The YWCA was one of seven organizations asked by the federal government to help deal with unprecedented changes on the homefront.4

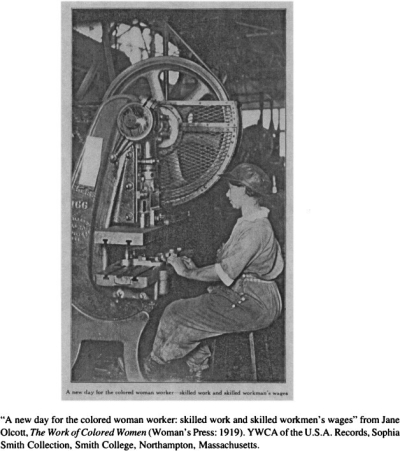

In response, the YWCA created the War Work Council (WWC) through their Industrial Program. The aim of the WWC was to address the cultural and demographic shifts caused by the increasing number of women in the industrial sector.5 Soon after the creation of the WWC, the YWCA addressed the tens of thousands of African-American women joining white women in industry jobs by appointing Eva Bowles the director of a new wartime Colored Work Committee (CWC).

Bowles, an educator and organizer for the YWCA’s segregated Harlem, NY branch, created the first national YWCA program work for Black working women.6 During a time of intense racial tensions and racism against Black Americans, Bowles and the CWC pursued an agenda of civil rights and “sought labor-based Black equality through an all-female space.”7

While history has focused on the struggles and civil rights advocacy of African-American veterans returning from the front in 1918, the YWCA’s programs for African-American women created a link between the labor and civil rights movements. The CWC’s advances towards interracial and class-conscious cooperation between female industrial workers are an important, yet often overlooked, piece of U.S. and YWCA history.

“Colored” branches of the YWCA were created as early as 1870, but were predictably marginalized by white national and local leadership. During the first World War, the CWC used funds to create what were essentially African-American parallels to the YWCA’s Industrial Program. Despite the fact that these “parallel” programs were segregated, they actively advocated for the advancement of Black members while their leaders demanded equal treatment and desegregation policies.

The Industrial Program provided members with recreation, meeting spaces, and education. What started as a place where women could learn to sew and study the Bible, turned into a space where women could learn about economics, history, trade unions and labor laws.8 Due to the wartime funding of the CWC, the money was available to provide substantive programs to support Black members of the YWCA.

Although these programs were their primary purpose, the CWC did not stop at providing segregated support to African-American women. The CWC actively challenged the white female workers’ prejudiced opinions of their Black coworkers. For example, in a wartime document - most likely given as a speech to white members of the YWCA - the author wrote: “One gravely questions the true patriotism of that class of women who hysterically rush into the frontline trenches of the industrial battle but throw down their arms and refuse to go into action if they find colored women seeking places as their comrades.”9 In addition to asking their Black members to disprove the negative associations assigned to Black women of the time, the CWC put the burden on white women to challenge their internalized racism.

Soon after the war ended in November of 1918, the CWC was decommissioned by the YWCA. However, the Industrial Program remained a branch of the YWCA with autonomy in its choice of leadership and content of their programming. In addition to their work with the CWC during the war, “Industrial Program staff were shaped by contact with working women and by the more radical strand of the Social Gospel movement, which urged engagement with social problems.”10

The first meeting of the YWCA National Industrial Council in 1922 solidified the Industrial Program’s dedication to racial justice. At this conference, the council guaranteed 2 out of 14 leadership seats would be permanently filled by African-American women.11 This move towards integration at one level of the YWCA would incrementally increase throughout the entire organization until the YWCA fully integrated in 1946. There is no doubt that the crux of the YWCA’s dedication to eliminating racism was forged through the efforts of Black women working in industry during World War I.

The work towards centering anti-racism at the core of the YWCA’s mission could not have been possible on the national scale without the dedicated efforts of local branches of the YWCA. The Yonkers branch of the YWCA was formed in 1892 and incorporated in 1895. Their 130 years of service began with their boarding house for young working women. The YWCA Yonkers Residence is still in service today.

Located in downtown Yonkers, the landmark building provides furnished rooms for single women of all ages and backgrounds. The housing project is “designed to help single women on their path to confidence and self-sufficiency.”12 With room enough for 48 women, the YWCA of Yonkers also offers supportive services to help women find permanent housing. Additional supportive services include assistance with finding employment, financial and empowerment workshops, access to a computer lab, and recreational activities.

The work being done by the YWCA of Yonkers to empower women and eliminate racism is a powerful contribution to the Yonkers community. Just as the YWCA of the late 1910s worked for a more equal and just society, so does the YWCA of Yonkers.

This article was researched and written by Olivia Keefe, CLIP intern at Yonkers Riverfront Library, currently in her fourth year at Sarah Lawrence College.

Endnotes

1 Frost, J. William, "Part V: Christianity and Culture in America", Christianity: A Social and Cultural History, 2nd Edition, (Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 1998), 476.

2 Our mission in action. YWCA USA. (2022, March 24). https://www.ywca.org/what-we-do/our-mission-in-action/

3 DeBruyne, Nese F. (2017). American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics (Report).

Congressional Research Service.

4 Browder, Dorethea. “A Christian Solution of the Labor Situation: How Working women Reshaped the YWCA's Religious Mission and Politics” (Journal of Women's History, Vol 19, Summer 2007) pg. 247.

5 Sims, Mary S. The Natural History of Social Institution: The Young Women's Christian Association (New York, 1935), pg. 181.

6 Browder, pg. 244.

7 Browder, pg. 246.

8 Browder, pg. 256.

9 "Industrial Movement Among Colored Women," Nov. 1918, typescript. Box 534, f. 2, YWCA, SSC.

10 Browder, pg. 254.

11 Browder, pg. 258.

12 “Housing for women” - YWCA advertisement flier, 2023.

More materials on the Industrial Revolution in the United States may be found in our catalog.

For additional materials on Yonkers history at the library, please follow this link.